Contents

- Foreword

- What truly separates architecture from building?

- Is Architecture necessary?

- Two perspectives

- On the Architectural Master Thesis

Foreword

I completed my Master Thesis in Architecture years ago, but only recently found time to revisit its arguments and theoretical explorations. This series is that reflection, written to clarify my own thinking and preserve it, lest it fade. Part 01 returns to the foundations of the discipline - or at least, my understanding of it.

What truly separates architecture from building?

“What is Architecture?” Too often, such a question serves more as rhetorical performance than a genuine inquiry. A grounded framing might be: What truly separates architecture from building?

One classical answer lies in Vitruvius’s triad: firmitas, utilitas, venustas-strength, utility, and beauty.1 A building must stand (firmitas) and serve its function (utilitas), but architecture insists on the third, more elusive quality: delight. When a designer attends to harmony, light, rhythm, or poetic integration with context, the act of construction crosses into the realm of art.

Laugier’s Primitive Hut offers a similar lens. In his 1753 Essai sur l’Architecture, he imagines a return to essential forms: column, beam, pediment.2 The point is not nostalgia for primitivism, but a search for architectural clarity and order, grounded in nature and necessity.

Later, Heidegger reframes the discussion altogether. In Building, Dwelling, Thinking, he reminds us that the German bauen (to build) is rooted in wohnen (to dwell), implying that building is inseparable from being at home in the world.3 Yet, a third act-thinking - is needed. Only when we pause to reflect on material, site, and lived experience does construction become architecture. In that moment, space is not merely enclosed, but gathered, becoming a vessel for care, memory, and possibility.

Building is the technical process of assembling walls, floors, roofs, and systems to enclose space and meet tangible needs such as safety, climate, or economy. It is assessed by how effectively it performs these duties. Architecture, on the other hand, is the intentional act of shaping that building beyond basic functionality. It considers proportion, light, movement, and context-how people perceive and experience space, how it relates to its surroundings, and how it might reflect and shape broader cultural or social values.

Is Architecture necessary?

Consider, then, the uncomfortable but necessary question: Is architecture truly necessary?

In practice, one can construct without ever invoking “architecture” - erecting walls, installing roofs, satisfying regulations, and meeting programmatic demands. That, by all practical definitions, constitutes a building.

And there is a fair argument to be made: most structures require little more than this. Given the very real constraints of budget, schedule, and necessity, efficiency often takes precedence. After all, we inhabit the interior, so why not focus our efforts there? Why labour over proportion and form when furniture, finishes, and fit-out can provide comfort and aesthetic satisfaction?

Some might go further and argue that architecture is, in fact, superfluous. History offers compelling evidence: many of the world’s most transformative ideas have emerged from the humblest of environments-anonymous offices, modular labs, rented rooms. MIT’s Building 20 stands as a potent example.4 Thrown up during wartime as a temporary research facility, it was a boxy, uninspiring shed by all appearances. And yet, its cheap partitions, ad hoc spatial arrangements, and sheer lack of preciousness created the perfect incubator for risk and innovation. It was there that breakthroughs in radar, linguistics, and computing quietly took root, despite its supposed lack of architecture.

Two perspectives

But here we must pause. What do such buildings, like MIT’s Building 20, actually reveal? That architecture is unnecessary? Or that we have perhaps misunderstood where its value truly lies?

If innovation can flourish in the absence of architectural intention, then perhaps architecture is not always needed to support what we already know how to do. But that does not mean it is without purpose. Instead, there are two perspectives that can reframe architecture’s relevance:

- Architecture as Public Service

- Architecture as Interrogation, Imagination

1. Architecture as Public Service

Any building unavoidably enters public life. It meets the street, casts shadows, shapes skylines, and frames the spaces through which we all move. House or monument, each adds a line to the collective text of a city, signalling welcome or exclusion, clarity or confusion, cohesion or rupture.

When design neglects scale, proportion, or context, that signal turns harmful. Boston City Hall and its windswept plaza alienate rather than invite;5 the demolished Pruitt-Igoe blocks showed how ill-considered form can compound social failure.6 Even Singapore’s Kallang Tennis Hub, oversized and indifferent, a drab blue and white box on the horizon, drags down the street’s rhythm.7 None of these buildings lacked design effort; they lacked design thought.

Because architecture inevitably affects the commons, it is not a luxury but a public service. Beyond meeting briefs or ticking code boxes, architects must anticipate a building’s ripple effects: on the passer-by, the neighbour, the larger city. To build responsibly is to recognise that architecture is never a neutral backdrop; it is an active participant in shaping collective life.

Hence the profession’s long training and licensure: not to gatekeep some esoteric art, but to ensure that those who mould public space do so with knowledge, judgement, and care.

2. Architecture as Interrogation, Imagination

The very way we conceptualise space-levels, rooms, corridors, walls-is not inevitable. These are constructs: artificial frameworks we have devised for efficiency, control, and habit. The flat floor, the rectilinear room, the ceiling as plane, all are conventions borne of material logic, industrial production, and regulatory clarity. Yet in standardising these elements, we also standardise how we live, move, think.

In that sense, “building” could also be defined not just as the act of assembling structure, but as the unquestioned reproduction of spatial norms: constructing space to meet a function, nothing more. And there is utility in this. A hospital needs legibility and functionality. A warehouse needs volume. Not every structure need aspire to delight.

Architecture then, begins where building leaves off. Not merely in decoration or refinement, but in interrogation. It questions the givens: Why must boundaries be fixed? Why must floors be flat? Why must space be divided as it always has been?

Architecture adds beauty, yes, but it can also provoke. A tilted wall, an unexpected courtyard, a roof that dips to greet a tree. These gestures invite new ways of inhabiting the world. They do not decorate function; they reimagine it. They open the door to other ways of being.

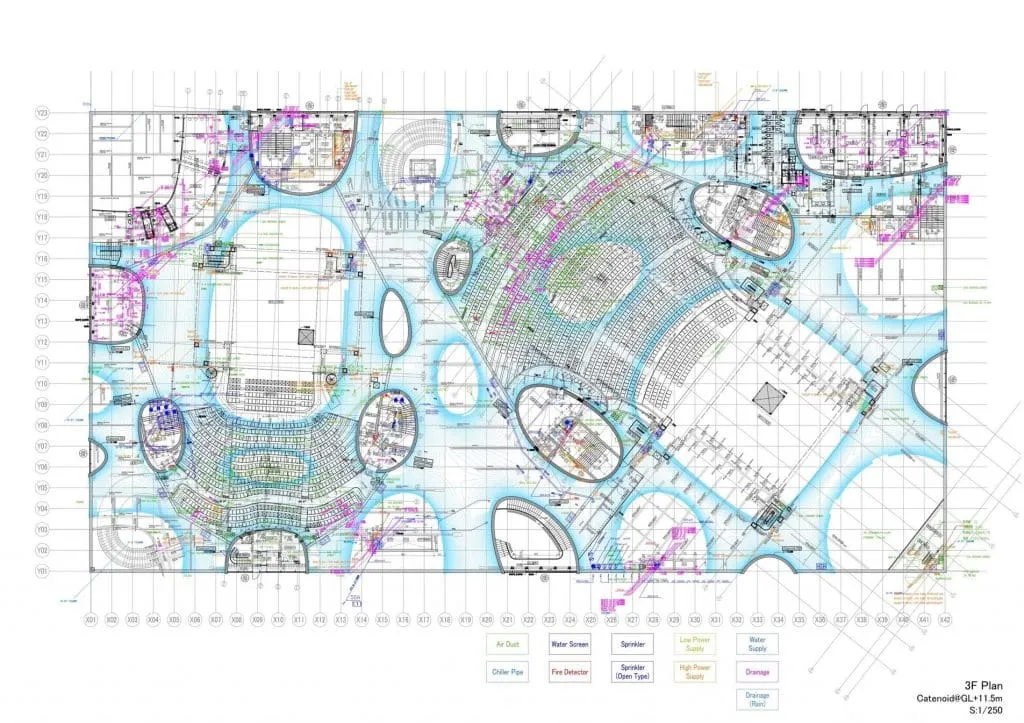

This is why we build spaces like Ryue Nishizawa’s Teshima Art Museum8-a delicate concrete shell with no overt economic function, yet profoundly moving in its silence and spatial purity. Or Toyo Ito’s Taichung National Theatre9, where walls, floors, and ceilings dissolve into one another in a continuous, fluid geometry. These are not just buildings; they are novel spatial experiences. Architecture, in such works, explores the emotional and psychological dimension of building-a medium through which space can move us, not just shelter us.

Teshima Art Museum - Photo by Denis Kovalev

National Taichung Theater, Third Floor Plan - Drawing from Drawing Matter

On the Architectural Master Thesis

It is with this understanding of architecture, as a spatial, cultural, and public act, that I approached my thesis.

Too often, architectural theses focus on solving complex programs or addressing social issues through design. These are important pursuits, no doubt, but they often place the discipline in service of external concerns - matters that may, in some cases, be more appropriately addressed by graduates of other disciplines. This, after all, is a Master’s Degree in Architecture, not Social Science, not Public Policy, not Engineering. And as such, I felt it important to turn my inquiry inward - not to abandon the real world, but to question the discipline in its current form:

What are the assumptions we build upon? How else might we design or construct space with the new knowledge, new perspectives, new technologies we have? And what new ways of living, thinking, dwelling might those alternatives make possible?

Such an investigation requires a broader lens, but one that ultimately sharpens its focus on architectural application. It calls for an engagement with history, theory, philosophy, law, sociology, and ethics, not as peripheral fields, but as essential frameworks for understanding how buildings emerge, and how they act in and upon the world.

… to be continued…

Footnotes

-

Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture. Translated by Ingrid D. Rowland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ↩

-

Laugier, Marc-Antoine. An Essay on Architecture. Translated by Wolfgang Herrmann and Anni Herrmann. Los Angeles: Hennessey & Ingalls, 1977 (originally 1753). ↩

-

Heidegger, Martin. Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper & Row, 1971. ↩

-

“MIT’s Building 20: Magical Incubator.” MIT Infinite History, September 2011. Video, 2:34; “Building 20.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, accessed July 8, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Building_20. ↩

-

Project for Public Spaces. “City Hall Plaza | Hall of Shame.” February 2023. https://www.pps.org/places/city-hall-plaza. ↩

-

Bristol, Katherine G. The Pruitt-Igoe Myth. University of California, Berkeley, 1991. See also: AD Classics: Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project / Minoru Yamasaki. ArchDaily, March 2015. https://www.archdaily.com/870685/ad-classics-pruitt-igoe-housing-project-minoru-yamasaki-st-louis-usa-modernism. ↩

-

“Expectation vs Reality: Kallang Tennis Hub.” Reddit Singapore, 2024. https://www.reddit.com/r/singapore/comments/1bz35l3/kallang_tennis_hub_expectation_vs_reality/. ↩

-

“Teshima Art Museum / Ryue Nishizawa.” ArchDaily, July 19, 2011. https://www.archdaily.com/151535/teshima-art-museum; Benesse Art Site Naoshima. “Teshima Art Museum | Art | Benesse Art Site Naoshima.” Accessed July 2025. https://benesse-artsite.jp/en/art/teshima-artmuseum.html; Benesse Foundation. “Exploring the Concepts of Teshima Art Museum.” ScholarSpace, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Accessed July 2025. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/items/22c4ea2c-97f2-4f0b-b92b-7ec1161c14b4. ↩

-

National Performing Arts Center. “Design: National Taichung Theater.” NPAC, accessed July 2025. https://www.npac-ntt.org/en/about/architecture/design; Pollock, Naomi. “National Taichung Theater by Toyo Ito & Associates.” Architectural Record, December 1, 2016. https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/12040-national-taichung-theater-by-toyo-ito-associates; WIRED UK, “The walls of this earthquake-proof theatre form ‘caves’ to amplify its sound.” May 9, 2017. https://www.wired.com/story/taiwan-national-taichung-theatre; Drawing Matter, “Structural Studies for National Taichung Theater.” July 6, 2018. https://drawingmatter.org/toyo-ito-associates-architects/. ↩